|

Genealogical Research: A Guide to Family History

Your

family history is the key to who you are, and learning more about your ancestors

is one of the most rewarding and enjoyable pastimes you will ever find, and most especially in historic Sullivan County! The research

can be fun. It is really important, however, to get off to a good start by approaching

the project in the proper manner. Doing so will help you to avoid headaches and

later confusion.

Definition of Family History

The phrase "family

history" is often used synonymously with the term "genealogy",

although a family historian is generally one who does family history for fun,

and a genealogist is typically a professionally trained researcher. Genealogy

is defined by Webster as: (1) An account or history of the descent of a person

or family from an ancestor; enumeration of ancestors and their children in the

natural order of succession; a pedigree. (2) Regular descent of a person or family

from a progenitor; pedigree; lineage.

Two Types of Family

History Research

You may choose to approach your research from one of

two different aspects: Ancestor-oriented or Descendancy-oriented. Most family

historians begin their research in an "ancestor-oriented" manner, which

indicates they are interested in learning about their direct-line ancestors such

as their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc. Those who are "descendancy-oriented",

however, are interested in researching all of the descendants of the progenitor

or oldest known person in any one given surname in their lineage. This latter

approach allows you to research collateral lineages, such as cousins, aunt, uncles,

etc., and is the more successful approach for the advanced researcher. Either

approach requires you to start with what you know about yourself and your parents,

working backward in time, generation by generation. Tips

for the Beginner - Remember the basic

4 Ws and a P - Who, what, when, where, and most importantly, prove it. Who

was your ancestor? What was his full name? What events took place in his lifetime?

When and where did these events occur? What documents do I have to prove this?

- Acquire

a Pedigree Chart, a basic form for recording your direct-line ancestors, beginning

with yourself and working backward in time. There are all kinds of charts that

will help you in your research, but this is the single most important chart you

can acquire.

- Set up a good filing system. You must

be organized, methodic and systematic in your approach to genealogy. In beginning

research, I recommend a simple alphabetical filing system by male head of household.

File your research notes, data, and photographs in acid-free, manila folders set

up accordingly.

- Plan to cite your sources. From

the early stages of your research, it is imperative that you record the titles

of books, microfilms, &c where you found your information. Your research is

much more rewarding and meaningful when you can prove what you have found, and

you won't have to backtrack later. The Chicago Manual of Style is a good

style guide showing the proper way to cite your sources.

- Dispel

the myths. Two of the most common "myths"

or family traditions are that of "Great-grandmother was a Cherokee Indian

princess," and "There were three brothers who came to this country."

These are often disproved, as family traditions have become somewhat glorified

over the years. We must write down family traditions as related to us by our forefathers,

but our foremost task as family historians is to prove what we have been

told.

- Do your "homework".

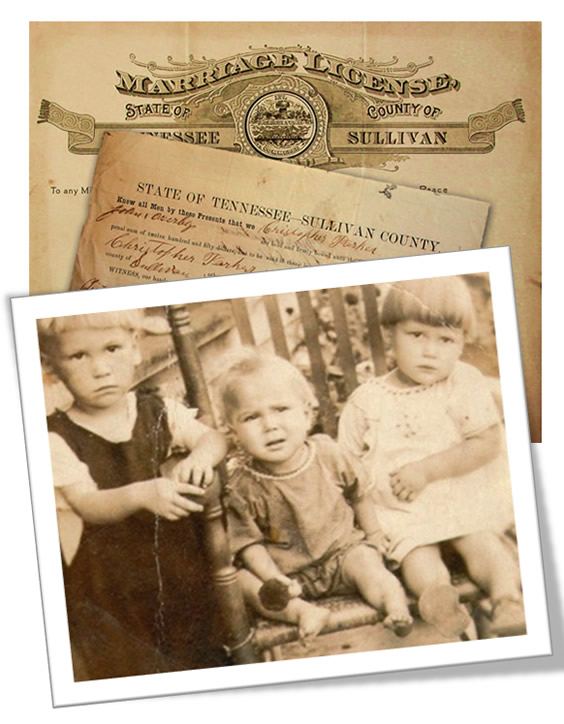

Start with yourself, working backward in time generation by generation. Dig out

those old trunks and shoeboxes of documents and pictures. Visit friends and relatives

to ask them about your parents, grandparents, and other ancestors. Keep notes

or tape-record your interviews. Visit family cemeteries and make photographs of

stones.

- Seek documented proofs by

visiting courthouse and libraries in search of actual proofs of your ancestors.

Examples of primary source documents are birth, death, and marriage certificates;

military records; census records; deeds; wills; estate settlements; school records;

and Bible records. An example of secondary source might be a printed publication,

such a family book in the local library.

- Practice

good etiquette in genealogical research. Be kind and courteous to the librarians

and court clerks, and remember that most of them do not have time to talk to you

in-depth about your family history. A general rule is refile your volumes in courthouses,

but don't refile in libraries. Do include a self-addressed, stamped envelope when

writing family members or libraries for information. Most importantly, be sure

to return anything you borrow from family members or friends the same day, and

never more than three days! This is a reflection on all family historians.

- Use

your on-site research time wisely when visiting the courthouses and libraries.

Put aside some extra money for copies instead of trying to abstract or transcribe

the information. Don't waste precious courthouse time by reading and analyzing

the documents on-site... Use that valuable time to photocopy as much as you possibly

can, and enjoy reading your material later that night.

- Don't

believe everything you see in print. Oh, yes,

cousin George may have written a book about your family history, but that does

not indicate that his work has been proven. Did he cite his sources? Find out

if he would be willing to share copies of his proofs.

- Acquire

a computer if at all possible. Today, even those

family historians with minimal computer knowledge are enjoying the Internet and

email aspects of computer technology. More advanced users will want to acquire

a good genealogy program for recording their family history. As of 2004, one of

the best genealogy programs on the market is RootsMagic.

- Keep

your Internet research in perspective. Be very focused in your searches when

turning to the Internet, and be guarded against wandering aimlessly around from

site to site. Again, remember that the family information which you may find on

the Internet may or may not be true.

- Store your research

in a temperature-constant environment. Storing your items in attics and basements

may shorten the lifespan of your documents and photographs.

- Share

and exchange with others. This is the greatest way to learn more about your

ancestors. A word of caution here to protect your copyrights: If you plan to publish,

consider waiting until your publication is in print before sharing your information

with others or putting it on the Internet.

- Align

yourself with a local genealogical society. Even

if you ancestors are not from the county in which you reside, join your local

society in the interests of sharing and exchanging the techniques of genealogy.

Remember that many of the basic genealogy principles you learn from your local

group may be applied to researching your ancestors who resided in another state

and county.

Remember, start with what you know

about yourself and work backward in time, generation by generation, seeking primary

source documentation to prove your ancestral connections. Enjoy

your family history, and good hunting!

Please visit the Sullivan County Department of Archives and Tourism Research Library. |